By triangulation I mean a diagram like below

|

| Figure 1 : a triangulation of the disc. |

|

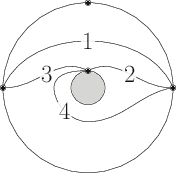

| Figure 2 : a triangulation of the annulus. |

From such a triangulation we can construct a quiver with relations. We denote this quiver $(Q_T, I_T)$, we take the surface as being understood. Let the set of vertices be indexed by the arcs in $T$. There is an arrow $i\to j$ in $Q_T$ if the curves $\gamma_i, \gamma_j\in T$ are incident to each other and form part of the boundary of a triangle $\triangle$ such that $\gamma_j$ follows $\gamma_i$ as you walk around the boundary of $\triangle$ in the counter-clockwise direction (recall that the surfaces are oriented). That definition may seem like a word jumble, so consider the following picture

$\gamma_i$ and $\gamma_j$ are point of the boundary of a triangle and $\gamma_i$ precedes $\gamma_j$, so we get an arrow $i\to j$.

At this point we have only constructed $Q_T$. The ideal $I_T$ is defined to be the composition of any two arrows that are defined by the same triangle. It is not obvious from this definition, but there are only three types of triangles in a triangulation

- those with only one edge from $T$, which defines no arrows;

- those with two edges from $T$, which defines exactly one arrow;

- and those with three edges from $T$, which defines three arrows.

At this point we are ready for examples. First going back to Figure 1

we get the following quiver

with $I_T = \langle ab, bc, ca\rangle$. In Figure 2, we hade

which defines the quiver

with $I_T = \langle ab, bc, ca\rangle$.

To clean up the statement of the next theorem, let me introduce one more piece of notation. Let $\mathcal C$ be the set of all homotopy classes of curves in the interior of $S$ with endpoints in $M$. The reason for doing this is that the following

Theorem.(BZ) Let $(S,M,T)$ be a triangulation of a surface as given above. The representations of $(Q_T,I_T)$ are in bijection with $\mathcal C\setminus T$.The theorem is in fact stronger. We can define a category with $\mathcal C$ being the objects and morphisms being elementary pivots. Then we actually get an equivalence of categories with the representations of $(Q_T,I_T)$. I discuss this in detail with additional references here. The punchline is this, instead of studying the quiver and its corresponding algebra directly, we should be able focus our study on the surface. For quivers of Dynkin type $A$, which arise as certain triangulations of the disc, this is overkill; but, for other quivers this gives us a new angle to attack their representation theory. In approximately 2 posts I will give a particular example where the surface presentation is especially useful.

At this point I should mention at least one caveat and 2 possible generalizations of this constructions. First the caveat. When defining the arrows, I choose to orient the arrows by traveling the boundary of a triangle in the counter-clockwise direction. There is no good reason to prefer this direction over clockwise, in fact, many people do use the clockwise direction. Hence, when reading related work using surface triangulations, it is important to look for which convention a person is using.

Now the generalizations. The simplest generalization is to consider other possible subdivisions of the surface. Here we required the subdivision to to have 3 boundary segments (at least one from $T$). We can just as easily define $m$-angulations in which the subdivisions have $m$ boundary segments (at least on from $T$). When the surface is a disc, the resulting algebras are $m$-cluster tilted.

The other possible generalization is to allow the points of $M$ to also belong to the interior of $S$. These surfaces are considered punctured. The notion of a triangulation must be suitably modified, the details were fully worked out by D. Labardini-Fragoso. The benefit of the punctured surfaces, beyond having more generality, is that certain triangulations of the punctured disc gives rise to type $D$ quivers. The exceptional Dynkin types $E_6$, $E_7$, and $E_8$ do not occur as triangulations of surfaces.

In the next post I will give an example where the surface realization is used to simplify a calculation.